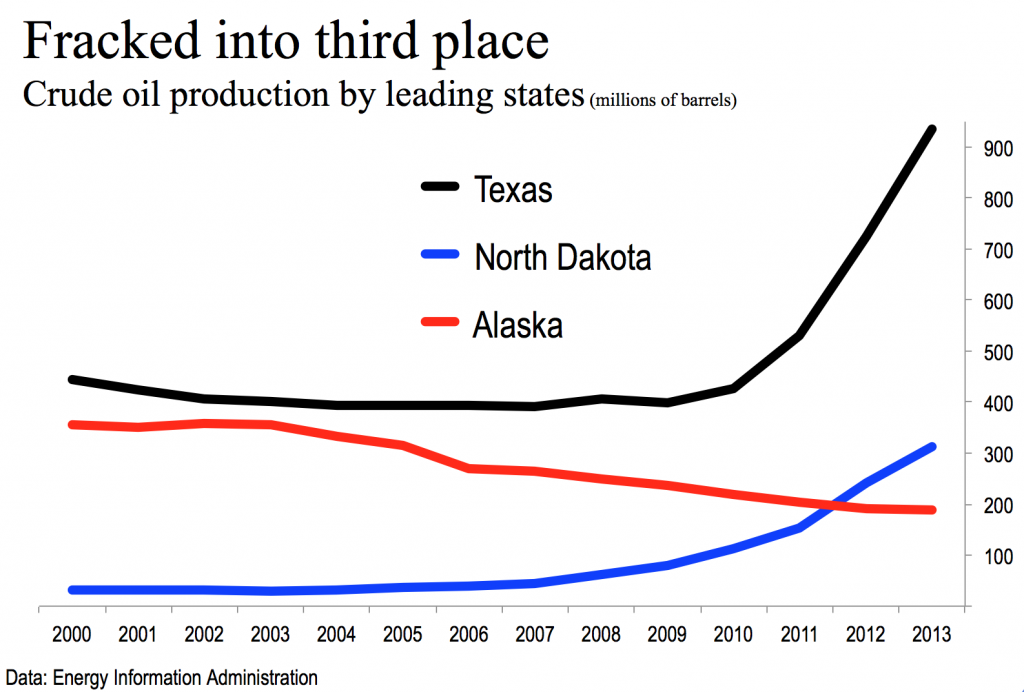

North Dakota passed Alaska in oil production on a monthly basis two years ago this month. So it is not news that Alaska, long a close second to Texas, remains No. 3.

North Dakota passed Alaska in oil production on a monthly basis two years ago this month. So it is not news that Alaska, long a close second to Texas, remains No. 3.

As recently as a decade ago, Alaska pumped almost 36 barrels of oil for every 40 pumped in Texas.

But advances in horizontal drilling and, especially, the rapid emergence of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) as a way of exploiting shale formations to produce both oil and natural gas have pushed Alaska ever more firmly into third place among oil-producing states. Last year Texas outproduced Alaska roughly 5 to 1. North Dakota, half a decade ago an insignificant producer, last year lifted two-thirds more oil than Alaska.

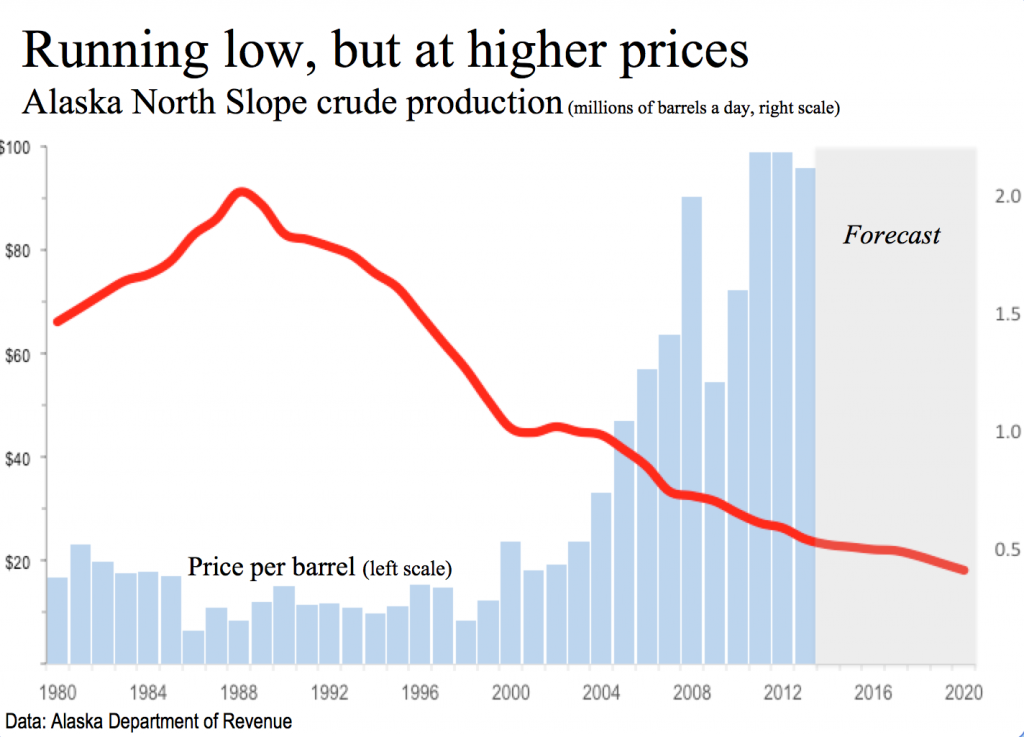

Alaska North Slope production peaked in 1988 at more than 2 million barrels a day. Alaska’s Department of Revenue forecasts that North Slope production will fall below half a million barrels  a day next year, and below 400,000 barrels a day by 2010.

a day next year, and below 400,000 barrels a day by 2010.

This steady erosion is not likely to be reversed any time soon. The U.S. Geological survey estimates that the Arctic holds 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30% of its gas. But the oil and gas is likely to remain out of reach for many years.

The head of Lundin Petroleum, a Swedish oil-exploration company focused on Norway, told Bloomberg News recently that oil production from the Arctic is unlikely in this decade and perhaps even the next. “The commercial challenges are just too big,” he said.

Royal Dutch Shell, which claims to have spent $6 billion in Arctic exploration over the years but has yet to drill a complete well, announced in January that for the second year in a row it won’t drill in Alaska waters. The company has been dogged by a series of environmental and technical problems. In a public relations fiasco, one of its Arctic drilling rigs ran aground while the company was trying to tow it out of Alaska waters to avoid Alaska taxes.

Other oil companies haven’t had much better luck. ConocoPhillips announced a year ago it would abandon plans to drill in a prospect about 80 miles offshore Alaska’s arctic coast because of uncertainty over governmental requirements.

When it comes to oil, Alaska suffers from what is known in economics “resource curse” or the “paradox of plenty.” The thesis is that countries or places with large amounts of non-renewable resources tend, for a variety of reasons, to be economically stunted. See this link for a discussion.

Alaska gets about 90% of its general-fund revenue from oil royalties and taxes. As the middle chart shows, the production decline in recent years has been offset to some extent by sharply higher prices.

Alaska gets about 90% of its general-fund revenue from oil royalties and taxes. As the middle chart shows, the production decline in recent years has been offset to some extent by sharply higher prices.

Alaska is a great place to live if you don’t like paying taxes. It is the only state that has neither a personal income tax or statewide sales tax. Property taxes can be high, but seniors and disabled veterans are excused from paying a large share of what otherwise would be due.

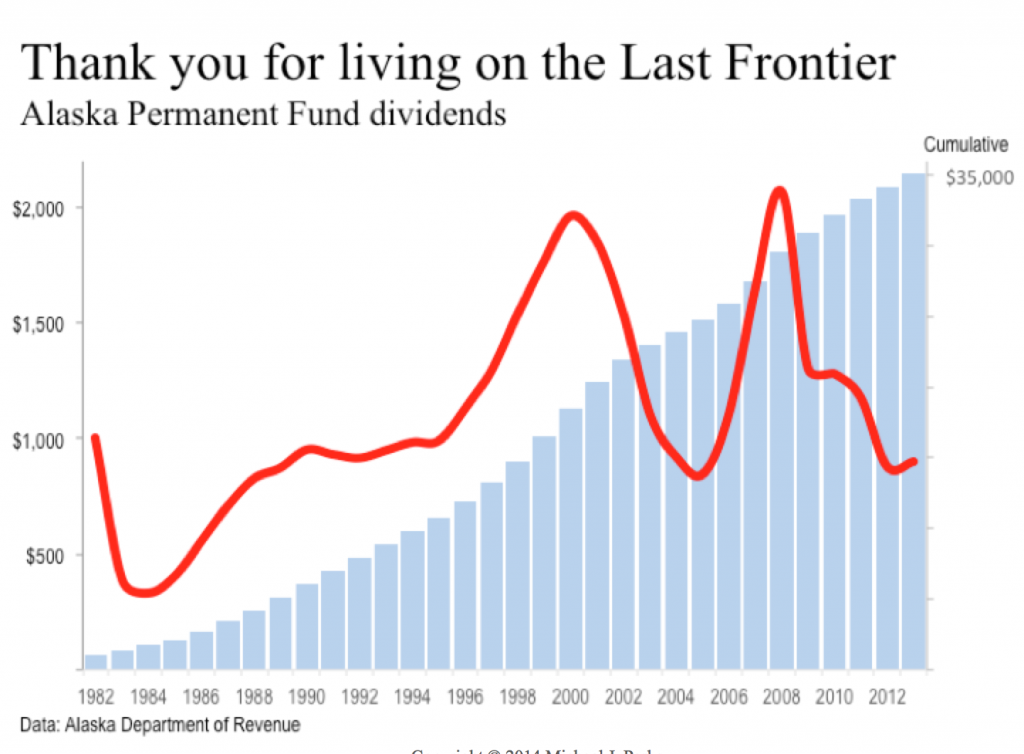

Thanks to the leadership of a far-sighted governor (Jay Hammond), Alaska in 1977 began socking away 25% of its inevitably declining stream of oil income into a fund to benefit future generations. The voter-approved constitutional amendment that created the fund prohibits spending of principal and requires, in fact, that the principal be protected against erosion by inflation.

The fund now exceeds $50.7 billion, or nearly $69,000 per head. From earnings over and above the amount needed to inflation-proof the principal, the fund began in 1982 paying out an annual dividend to every permanent resident. The first dividend was $1,000, the next two were under $400.

Not counting a $1,200 energy rebate in 2008, dividends over 32 years have amounted to about $35,000 per head, or more than $1,000 per year.

Alaska’s best hope for offsetting the continued oil-production decline is development of Arctic natural-gas reserves. Alaska’s Legislature has just approved a plan to spend up to $500 million for early engineering and design of a pipeline that would bring Alaska natural gas from the Arctic to Nikiski on the Kenai Peninsula, where it would be liquified for export to Asia. Cost estimates range up to $65 billion. Whether developing Alaska’s gas reserves makes economic sense when gas is so abundant in the Lower 48 remains to be seen. Stay tuned.