As I mentioned on KUOW’s Weekday program today, I was delighted to read in today’s Financial Times* that manufacturing employment has grown faster in the U.S. during this recovery than in any other advanced country.

As I mentioned on KUOW’s Weekday program today, I was delighted to read in today’s Financial Times* that manufacturing employment has grown faster in the U.S. during this recovery than in any other advanced country.

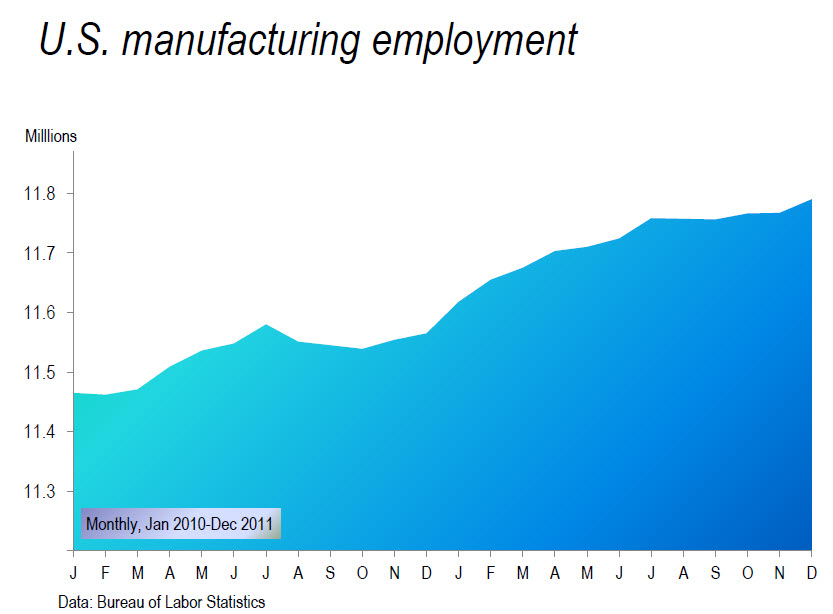

From January 2010, employment in U.S. factories has risen by 2.9% to nearly 11.8 million (chart). The comparable change for Germany is 2.4%, for Canada 1.9%. In Japan, Italy and France, by contrast, manufacturing employment has fallen.

In fact, reports the FT, the U.S. has added more factory jobs since the beginning of 2010 than the rest of the globe’s richest countries (the Group of Seven, or G7, comprising the six countries mentioned plus the U.K.) combined.

I’m not Dr. Pangloss. U.S. factory employment has been on a downward trend for more than 30 years. Factory head count is down 40% from its post-World War II peak, which occurred in mid-1979. Despite gains the past two years, factory employment is still nearly 2 million below where it was before the Great Recession/Lesser Depression.

But a couple of angles in the FT article caught my eye, partly because they go against conventional wisdom. Example: The lack of wage growth in the U.S. is deplored endlessly, but it is helping make the U.S. more competitive. The FT says unit labor costs in the U.S. fell 11% in dollar terms in the period 2002-2010. In Japan they rose 3%. In Germany, they soared 41%, in part because of the strength of the Euro, roughly at parity with the dollar in 2002, now at $1.28.

Cheap Chinese labor? Not as cheap as it used to be. The FT notes that Chinese factory pay has been rising 15% or more annually for at least the past eight years. No wonder some companies have decided to bring work back to the U.S. from outposts in China and elsewhere.

Even higher oil prices make a difference. Hauling raw materials across the Pacific to China and hauling finished goods back made a lot more sense when oil was at $25-30 a barrel than at today’s price. The U.S. shale-gas boom, which has pushed down the price of natural gas and reduced related industrial energy costs, also favors the U.S.

Cash-laden U.S. companies are spending heavily on equipment and software to boost productivity. That means U.S. factories can churn out more stuff without adding a lot more people. Anyone who has ever toured Boeing’s factory for wide-body jobs in Everett will tell you their first surprise is how few people they see in some of the world’s largest buildings.

U.S. factories employed nearly 20 million people in mid-1979. Those days are gone forever. That said, it is encouraging to know that we are doing better on this score than other advanced economies.

*Registration required; FT.com allows retrieval of several Financial Times articles a month before a pay-wall is encountered.