Prompted by reading, I’ve been thinking about an essay arguing that today’s exceptionally low interest rates are a form of default.

Prompted by reading, I’ve been thinking about an essay arguing that today’s exceptionally low interest rates are a form of default.

The idea is far from original. Op-ed pieces in the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal have seeded my thinking.

An op-ed in today’s Wall Street Journal by George Melloan will go into the stack of clippings I will review before I write my essay. Melloan, a former Journal columnist and deputy editor, argues in favor of a bill that would strip the Federal Reserve of its dual mandate (price stability and full employment). Here are a couple of paragraphs from Melloan’s piece:

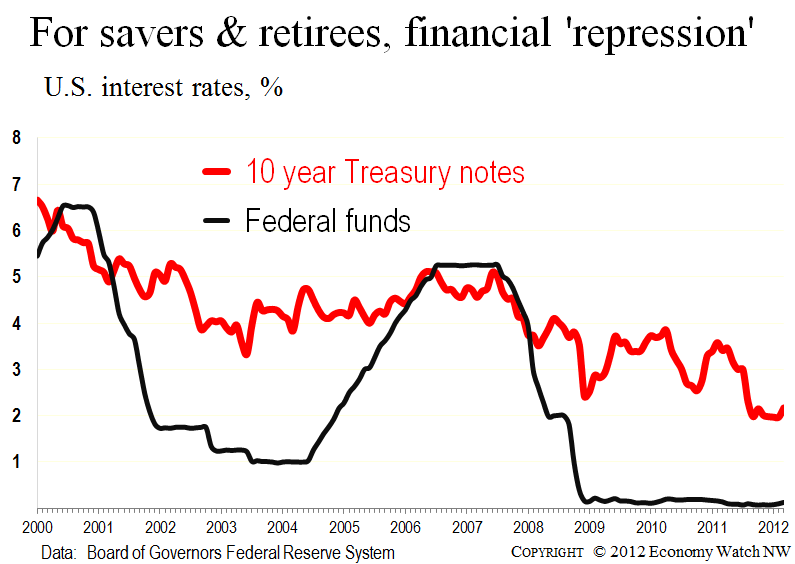

The Fed doesn’t have the capability to maintain full employment and its efforts to do so have produced nothing but trouble. That mandate is the justification the Fed has cited for the near-zero interest rate policy it adopted in 2008 and promises to continue through 2014.

How has that worked out? We are suffering through one of the weakest recoveries on record. Unemployment remains above 8% and would be even higher were it not for the number of workers who have given up looking for a job. Meanwhile, the Fed’s near-zero interest rate policy has reduced returns on the savings of individual investors and given managers of defined-benefit pension funds multibillion-dollar headaches as they struggle to earn enough on their portfolios to meet their obligations.

Melloan goes on to note that while low rates haven’t solved the problem of weak employment growth, they have provided cheap financing to Uncle Sam. Imagine how much higher the interest-rate bill would be if soaring Federal debt carried more normal interest rates. You don’t want to know.

How is this a form of default? Look at it this way: Ultra-safe investments such as Treasury bills and notes are paying less than the inflation rate. Lend your money to Uncle Sam at anywhere from 30 days to up to 10 years these days, and the one thing you can be pretty certain about is that in terms of spending power, at maturity you will get back less than you put in. That, to my mind, is a form of default.

The Fed’s low interest-rate policy means that if you want to protect yourself from inflation, you are forced to go out on the risk scale, buying corporate bonds or dividend paying stocks. Not a particularly attractive option, given the bad odor that has emanated from Wall Street the past few years.

I’m a little uncomfortable agreeing with Melloan, who probably would have fit right in with Hoover’s secretary of the Treasury (“Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate. It will purge the rottenness out of the system” — Andrew Mellon, November 1929). But he is right that today’s low rates are penalizing retirees and savers and facilitating the expansion of deficit spending. Low rates are also making more severe the fiscal squeeze on state and local governments on the hook for defined-benefits pensions.

The longer interest rates stay low, by the way, the more difficult it will be for the Fed to unwind its policy stance. Low rates have helped inflate the prices of stocks as well as other asset classes. These prices will be at risk when rates return to whatever is normal. The fragile recovery in the U.S., to say nothing of the creaking economies in Europe, would also be at risk.